"S and L Hell" by Kathleen Day

Above: "S and L Hell - The People and the Politics Behind the $ 1 trillion Savings and Loan Scandal" - Kathleen Day, 395 pages. I completed reading this book in December 2024.

The Savings and Loan (S and L) Crisis produced the greatest collapse of U.S. financial institutions since the Great Depression.

The Savings and Loan (S and L) Crisis produced the greatest collapse of U.S. financial institutions since the Great Depression. Over the 1986–1995 period, 1,043 thrifts (S and L nickname) with total assets of over $500 billion failed. The large number of failures overwhelmed the resources of the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), so U.S. taxpayers were required to back up the commitment extended to insured depositors of the failed institutions. As of December 31, 1999, the thrift crisis had cost taxpayers approximately $124 billion and the thrift industry another $29 billion, for an estimated total loss of approximately $153 billion.

The problem geminated during the 60's/70's era of volatile interest rates, stagflation, and slow growth. In the early '80's, S and L's, also referred to as thrifts, were principally mortgage lenders. When rates began to rise to fight inflation, S and L's had to raise the rates they paid on deposits. Since most of the S and L assets at the time were fixed rate mortgages, S and L's experienced an interest rate squeeze that eroded/eliminated profitability.

When the problem of the interest rate squeeze became apparent, regulators, not having sufficient funds from the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC) to close banks and pay off depositors, and unwilling to force politicians to realize that the taxpayers would have to step up to resolve the crisis, began to allow S and L's to pursue highly speculative investment strategies, hoping the S and L's could work their way back to profitability. This softening of regulatory oversight actually prolonged and deepened the problem as interest rate squeeze losses quickly morphed to bad loan losses and fraud.

The book describes how so many of the major participants--the regulators, politicians, and S and L operators themselves--chose to do nothing as they watched problems mount and taxpayer liabilities grow. That choice was dictated by a variety of motives: greed, political self-interest, and even misguided good intentions. Whatever the motives, this collective interest in hiding the debacle made it certain that the industry's final fall would come with an enormous cost, one that would force politicians and regulators that professed a free market philosophy essentially to nationalize a majority of the nation's thrifts.

Day's screed is a journalist's account of the factors that brought America's S&Ls to crisis. Where other analysts have focused on the predators whose buccaneering became a public scandal, Washington Post correspondent Day offers detailed, documented perspectives on a wealth of political influences, refuting the notion that economic reverses, fraud, or junk bonds were primarily responsible for the solvency woes of thrift institutions. After providing a back-to- basics rundown on the industry's origins as a Washington-favored source of residential mortgages, she addresses the rush to deregulation that began toward the beginning of the Reagan Administration and that set S&Ls on a slippery down-slope during the 1980's. Among other unintended consequences, Day points out, the introduction of laissez-faire triggered a scramble for brokered deposits which encouraged risky lending practices that soon resulted in soaring default rates.

Day attributes the paucity of disclosure and seizures to a host of causes. To begin with, Reagan-era regulators were incented to avoid action that might increase budget deficits; accordingly, they endorsed stopgap measures as well as accounting gimmicks designed to help troubled associations weather interest-rate storms and, later, to paper over capital shortfalls. In the meantime, the author explains, S&L executives and their lobbyists kept pressure to remain open on lawmakers beholden to them because of campaign contributions.

The overdue tab run up by incompetently regulated and managed thrifts was finally presented to taxpayers following the 1988 presidential election. Day's book was published in 1991. Day believed, noting ongoing regulator bungling, that the true cost of the S and L resolution would exceed that approved by Congress in 1989 via the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act (FIRREA). Day thought that losses, over time, from the S and L crisis could reach $1 trillion. However, the $153 billion in losses to taxpayers and surviving thrifts still stands.

Day's account is a human story. She documents the players, their interactions, scheming and procrastinating legerdemain with detail born of solid research. The S and L crisis seems long forgotten in the wake of The Great Recession which began in 2007. Notwithstanding, "S and L Hell" is an important fable about the dangers and pitfalls of procrastination and regulatory kicking the can down the road.

S and L Industry Denouement (Post Kathleen Day book)

The Savings and Loan industry emerged from the 1980s-early 1990s crisis—marked by over 1,000 failures and $124 billion in taxpayer costs—severely weakened but stabilized by 1995. The Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) closed on December 31, 1995, having resolved 747 failed S&Ls with $407 billion in assets. Post-1995, the sector focused on core residential lending under stricter regulations, but faced ongoing consolidation through mergers, conversions to commercial banks, and acquisitions by larger banks. Today, S&Ls represent a niche within the broader banking landscape, emphasizing mortgages and community banking, with diminished distinct identity.

Addendum:

American Savings of Florida - S and L Crisis Case Study

Introduction

From 1986 to 1994 (with a hiatus in New York City between 1988 and 1991) I was a player in the thrift industry. This period was at the height of the thrift crisis as described in "S and L Hell," by Kathleen Day.

For three years, from 1986 to 1989, I was CEO of Citicorp Savings of Florida (at CSF), a troubled thrift acquired by Citibank with government financial assistance in 1984. By purchasing thrifts held in government receivership Citibank was able to gain coveted but then prohibited interstate branch banking permissions in California, Illinois and Florida.

Beginning in 1986, I headed the second wave Citibank management team assigned to the failed Biscayne Federal Savings Association. Biscayne, name changed to Citicorp Savings of Florida (CSF), had assets of $2.1 billion and deposits of $1.7 billion, with thirty branches at time of acquisition. After Citi's purchase of Biscayne, the thrift had plenty of capital. We were not trying to save an institution from bankruptcy, but to render it a profitable contributor to Citibank's interstate banking effort.

During my three years at CSF, we improved the bank's profitability through a combination of cost reductions, new loan programs, and improved interest rate risk management. I was proud of the team I put together at CSF which included a former Citibank boss of mine, Charlie Kelly. I had worked for Charlie, CEO of Citicorp Australia, as his Credit Policy head, from 1974 to 1976.

The Feeler to become CEO of American Savings of Florida (ASF)

In the fall of 1991, while working as Citi's US Consumer Group Credit Policy head in New York City, I was contacted by Miami based John Mestepey of the search firm A.T. Kearney and asked about my interest in assuming the position of CEO of American Savings of Florida (ASF), a troubled Miami thrift. Much of my career with Citi had been working from the CEO position to fix troubled businesses (FNCB Finance, Philippines, Citicorp Credit KK, Japan, and CSF in Miami). I felt comfortable in business turnaround situations, so Mestepey's proposal seemed worth exploring. After weighing the pros and cons for a few days I called Mestepey and expressed my interest in exploring the offer.

ASF - Pros and Cons

Pros. I was in a senior staff position at Citi New York headquarters. I missed being a CEO doing business "turnarounds." Margaret and I loved our three years in Miami from 1986 to 1988. Phoebe was in college at Georgetown. Our move wouldn't affect her one way or the other. Jake would graduate from Staples Highschool in Westport, CT in the Spring of 1992. Margaret and he could stay in Westport until Jake's graduation and then she and Jake could join me in Miami. Going in salary for the ASF job offer was a step up from where I was at Citi and competitive with average salaries at the time for comparable thrift CEO positions. More important was the potential upside from stock options offered as part of my compensation package should the bank turnaround succeed. Margaret was eager to return to her daily tennis regimen in Miami.

Cons. ASF was a publicly traded troubled thrift. In November of 1991 ASF shares were selling for $0.17 a share. ASF's 40% owner, Enstar Group, had recently declared bankruptcy. The bank's regulator, The Office of Thrift Supervision, had recently imposed a Cease-and-Desist Order on ASF and ordered a reconstitution of the bank's board and management. The market was betting on a seizure of ASF by its regulator, the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) followed by a transfer ASFs assets to the FIRREA created Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) to be sold. As is well chronicled in Day's book's, shutdowns of troubled thrifts during this period were de rigueur. Would I be given the time to implement the business plan I had drawn up?

I accept the ASF offer

I interviewed with the ASF's newly constituted board, including ASF Chairman, and Enstar Group bankruptcy trustee, Nimrod (Rod) Fraser. I flew to Atlanta to interview with Jack Ryan, Regional Head of The Office of Thrift Supervision.

In early November 1991 I was called by ASF board member Jim Davidson. Jim: "Steve, you are currently number two in consideration by the board for the CEO position. Two board members, including me, believe you are the best person for the job. The other three board members prefer the other candidate. I have been able to persuade the board to take another look at both candidates. Steve, the board would like you to draw up a hypothetical business plan for effecting the turnaround of ASF."

I studied carefully ASF's numbers and calculated a way out of the room for ASF over a four-year recovery period. I prepared a plan - a four pager - as requested and sent it to Jim. The plan included re-legitimizing ASF's governance structure, restructuring the balance sheet, cost cutting, bad debt rationalization, growing the deposit base, implementation of new business lines, including HELOCs, and bringing interest rate risk and credit risk management up to standard, and release from a regulatory Cease-and-Desist Order along with a timeline showing benchmarks of progress along the way of recovery.

Near the end of November 1991 Jim called back: "Steve, the board loved your business plan for ASF. We would like to extend to you an offer to join ASF as CEO. By the way, Steve, the board rechecked your competitor's educational credentials and found that the school which he had claimed issued him a degree denied awarding him such a degree. It's good that we took a second look at both of you."

After confirming from ASF's board that I would have an adequate pool of stock options to offer top talent to come work at ASF, we decided to leave Citi after twenty years.

Nimrod Fraser, Enstar bankruptcy trustee; Chairman, ASF Board of Directors, 1991 to 1994.

Above: Jim Davidson, Member Board of Directors, American Savings of Florida.

American Saving of Florida - Historical Overview

Shepard Broad establishes ASF

Above: Shepard Broad. Founder, American Savings of Florida.

American Savings of Florida (ASF) was a savings and loan institution established in Miami, FL in 1950. The bank's founder, Shepard Broad, was born in Minsk, Russia in 1906 where he trained as a tailor's apprentice. Eastern Europe offered little opportunity to a Jewish boy, so, at the age of fourteen, Shepard joined the mass migration to North America. He ended up in Canada, sponsored by the Canadian-Jewish Immigration Society, and eventually made his way to New York City.

Shepard practiced law in New York City from 1928 to 1940 whereupon he moved to Miami. He was admitted to the Florida bar in 1940. He started his own law firm, Broad and Cassel, which continues to this day with offices throughout Florida.

A prescient businessman, Shepard located ASF branches for his new thrift at strategic locations of retirement communities throughout south Florida. By 1983, ASF's deposit levels averaged $100 million per branch. Through 1983, ASF was a successfully run savings and loan institution, taking in deposits and extending residential mortgages. When ASF's profits were squeezed by rising interest rates in the early '80's, as it was swept up in the growing S and L crisis, Shepard Broad went in search of additional capital. In 1983 he found his source of capital: Cincinnati businessman, Marvin Warner.

Marvin Warner and ESM

Above: Marvin Warner, Investor, American Savings of Florida, 1984.

Marvin Warner, a savvy and successful entrepreneur, was a politically influential man, prominent in Florida and Ohio as well as his native Alabama. Warner was President Jimmy Carter's US Ambassador to Switzerland from1977 to 1979.

In 1983, Warner bought 25% of ASF. He put his shares in a joint trust with the Broad family. Warner became Chairman of ASF and Warner business partner Ronald Ewton, co-founder of Miami securities dealer ESM Government Securities, Inc., joined ASF's board.

Encouraged by Warner, in 1984 ASF invested $108 million of its Treasury securities in ESM reverse repos. When Warner urged ASF to acquire Tampa based S and L, Freedom Savings and Loan, Shepard and his son Morris, then CEO of ASF, had misgivings. They considered a Freedom bid to be hostile and didn't want to be involved. Increasingly wary of Warner's involvement in ASF, the Broads began to distance themselves from the Ohio businessman. In response, Warner decided to try to buy out the Broads. The Broads fought back and decided to buy out Warner. The Broads sought the approval of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, unbeknownst to Warner, to use company funds for the buyout, as long as they replaced the capital later. The regulators, very supportive of the Broads, swiftly came back with their approval. The Broads declared victory.

In early 1985, Warner sold his stake in American Savings. Shepard Broad, founder of American Savings, regained control of ASF. Following Warner's departure from ASF, the Broads decided to withdraw their $108 million position from ESM. The withdrawal began the chain of events that caused the unravelling of ESM. ESM was unable to make good on the whole amount it owed to ASF and filed for bankruptcy.

Throughout ESM's nine-year history, there were strong and continuing links between Warner and ESM's CEO, Ronald Ewton. Ewton had been introduced to Warner by Miami attorney, Stephen Arky, Warner's son-in-law. Arky took his life in July of 1985 in the wake of ESM's fall. Arky left a suicide note denying any knowledge of ESM's fraud.

Though not widely publicized in the histories of the S and L Crisis, in a very real way, ASF's recalling the $108 million that it had invested with ESM triggered the broader S and L Crisis discussed in Day's book. The ESM collapse sent shock waves through the US investment system and triggered the 1985 Ohio banking crisis which became a trip wire for the national S and L crisis to follow. Ohio's Home State Savings Bank, owned by Warner, like ASF, was also doing substantial business with ESM. After ESM failed, Home State suffered a loss of $150 million. A run on Home State ensued and the bank was closed on 09 March 1985. Bank runs occurred on other institutions insured by the Ohio Deposit Guarantee Fund after it was revealed that the fund had insufficient resources to pay off Ohio savings bank depositors.

On 15 March 1985, Ohio Governor Richard Celeste declared a three-day banking holiday for the seventy other savings institutions covered by the Ohio Deposit Guarantee Fund. Home State was later sold. Some of the seventy surviving banks merged and all surviving Ohio savings and loans joined the FDIC to obtain deposit insurance. Day's book chronicles Celeste's panicked call to Paul Volker, head of the US Federal Reserve System. Volker's response to Celeste was along the lines of "your cause is just but I can do nothing for you." The Ohio thrift crisis is marked as the first event of the S and L crisis and while Warner's downfall would have happened sooner or later, it was ASF's call on its government securities investment with ESM that triggered fall of ESM and Home State Savings Bank.

ASF wrote off $68.7 million pursuant to the ESM scandal. ASF survived, and later recovered $22.5 million in a settlement from Grant Thornton, the accounting firm that audited ESM. ASF reported a net loss of $48.8 million in its second quarter ended March 31, 1985, compared with a profit of $3.1 million in the period a year previously. Marvin Warner was convicted in 1987 for crimes related to the ESM scandal. Warner spent three years in a federal prison. He died in 2002.

The regulators had endorsed the Broads in their effort to regain control of ASF in 1985, but ASF's need for additional capital, especially considering its losses from the ESM transaction and a continuing squeeze on margins, did not go away. The Broads started looking for another partner or buyer for ASF. And, in the third quarter of 1988, they found one: Enstar Group Inc.

Enstar Group Inc.

Alabama based Enstar Group, formerly KinderCare, of Montgomery, Alabama, bought American Savings during the third quarter of 1988 for $138 million and converted the heretofore publicly traded ASF into a private company. Richard Grassgreen was Enstar CEO. Harris C. Friedman, formerly an economist at the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, was appointed as Chairman and CEO of ASF in April 1988.

After its acquisition by Enstar, ASF began to invest in junk-bonds underwritten by Drexel Burnham and Lambert. ASF parent, Enstar was one of the biggest buyers of high-risk junk bonds sold by Drexel. By the end of 1988, ASF's junk bond portfolio was valued at $209 million.

In 1989, the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (FIRREA), legislation to address the S and L crisis, was passed by Congress. A key stipulation of FIRREA was that all S and L's sell their junk-bond portfolios by 1994.

Enstar, which reported a profit of $42 million in 1988, reported a loss of $150.6 million in 1989. Enstar reported that $89 million of its $150.6 million 1989 loss came from write-downs on the junk-bond portfolio it had purchased from ASF pursuant to the FIRREA requirement that ASF divest from its junk-bond portfolio.

In February of 1990, a financially troubled Enstar noted its intent to sell ASF, either through a public offering or by spinning off the institution to Enstar shareholders. Enstar's notice of intent to sell ASF came after a $91 million loss reported by ASF in the third quarter of 1989. As of 30 September 1989, ASF had $159.3 million in capital representing 2.6 percent of its assets. Regulatory capital requirements at the time were 1.5% of assets. As of 30 September 1989, the very thinly capitalized ASF had almost $5 billion in assets.

In May of 1990 ASF reported a profit of $698 thousand for the most recent quarter. ASF CEO Harris C. Friedman said the results reflected the first full quarter of operations since the company underwent a major balance sheet restructuring in 1989. As of 31 March 1990, ASF had total assets of $4.8 billion, making it the second-largest savings and loan association in Florida.

In November of 1990, Harris C. Friedman, chairman of ASF resigned after regulators admonished ASF about loan transactions with Enstar Group Inc. Stephen Lazovitz, a member of ASF's board, was named chairman and acting chief executive of ASF. Vice Chairman Edward Mahoney was named president and chief operating officer.

In December of 1990 ASF announced that its federal regulator, The Office of Thrift Supervision, (OTS), was to have a greater say over dealings between ASF and Enstar. OTS regulators, led by Atlanta Regional Head, Jack Ryan, had issued a supervisory directive in October raising objections to a $210 million note issued by Enstar in December 1989 in exchange for ASF's portfolio of junk bonds. Enstar fell behind on its payments on the note in October. Regulators at that time asked ASF to consent to a cease-and-desist order that would block it from undertaking any unsafe or unsound dealings with Enstar. The order prohibited ASF from engaging in further transactions with Enstar without regulatory approval.

Enstar declared bankruptcy in May 1991. Nimrod T. Fraser, Alabama based financier, property developer and investor, was appointed as chairman and bankruptcy trustee for Enstar. ASF became a public corporation listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange. 60% of ASF's shares were "spun off" to Enstar shareholders. 40% of the bank's shares were retained by the bankruptcy estate of Enstar Corporation. With the active involvement of federal thrift regulators, the Enstar bankruptcy trustee recast the ASF board of directors. Summer of 1991 ASF's new board began a search for an ASF CEO.

In November of 1991, ASF filed a $1.2 billion suit accusing Michael R. Milken, the imprisoned former junk-bond executive, of looting American Savings. The suit contended that Milken and his brother, Lowell, who also worked at Drexel, concealed, destroyed and created bogus records for ASF. The suit said that Mr. Milken manipulated the junk-bond market and sold worthless securities. The suit said such actions were largely responsible for ASF's loss in 1990 of $73 million, which forced it to sell branches and cut costs under pressure from federal regulators.

At year end 1991, ASF had total assets of $3.4 billion, deposits of $2.4 billion, 30 branches throughout south Florida, and 631 employees.

Fixing ASF - 1991 to 1995 - The Team

I was able to persuade some highly talented people to join me and help effect the turn-around of ASF.

Ralph Kravitz, a former boss from Citicorp Australia days (1974 to 1979) spent three months in Miami on a contract basis to spec out cost rationalization opportunities and to optimize back office and systems.

Hank Williams joined as mortgage head. Hank had worked for me as NC/SC region mortgage head when I was a McLean, VA based division executive charged with Citi's mid-Atlantic mortgage business in 1986. Hank had followed me to Florida in late 1986 to occupy the same position when I was CEO at Citicorp Savings of Florida, based in Miami.

Chuck Holland joined as EVP, Corporate Strategy and Support. Chuck, a Cal Tech graduate, and I worked together in Sydney, at Citicorp Australia, for Ralph Kravitz in the mid '70's. Chuck was analytically astute (read, really smart) and had deep knowledge of data processing systems.

John Camino, who was data center manager at Citicorp Savings of Florida, joined ASF as CIO.

Robert Arena, who worked with me at CSF, took the commercial lending head function.

Tom Chen, a marketing expert who worked with me in Asia and at Citicorp Savings of Florida, joined as second in charge of ASF's branch network.

Logos Yeh, internal auditor at Citicorp Savings of Florida, came aboard in the same position at ASF.

John Glade a HELOC expert, had followed me and Hank Williams from McClean to Citicorp Savings of Florida. John signed on at ASF to launch a second mortgage program.

Citi New York employee Gary Laurash came aboard as head of Treasury following the untimely passing of Charlie Kelly who had earlier accepted the Treasury position of ASF.

Treasury Back story #1: Charlie Kelly, my former boss as CEO of Citicorp Australia, joined Citicorp Savings of Florida (CSF) as Treasurer in 1986. I had recruited to him to CSF from a Citi Treasurer position in Europe. When I left CSF in late 1988 to take the New York Credit Policy assignment, Charlie also left CSF to assume the Treasurer role for the New York City Retail Banking Division of Citibank. On taking up the ASF CEO position in 1991, I persuaded Charlie to join me again, this time at ASF as Treasurer. Sadly, Charlie had a heart attack in New York City and passed away before taking up his position at ASF. Margaret and I attended Charlie's funeral in New York City in December 1991.

Treasury Back Story #2: Gary Laurash was friends with Herman Sandler, CEO of the New York investment banking firm, Sandler, O'Neill and Partners. Four of five times during my tenure at ASF I would join Gary and Herman for a chat, sometimes over lunch, during Herman's visits to Miami. Unhappily, Herman Sandler, and sixty-five Sandler O'Neill employees, lost their lives during the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks at the World Trade Center. The firm's offices were located on the 104th floor of the World Trade Center's South Tower. The surviving members of the firm decided to set up the Sandler O'Neill Foundation to provide support for the families of the deceased employees. This initiative has since paid for the college education of 54 children of the fallen workers.

Four key senior veterans of ASF stayed on to be part of the ASF turnaround team: Alan Goldstein, General Counsel; Linda Haskins; CFO; Barbara Mahoney, Retail Branch Head; and Tom Dorsey, Premises Head. All performed admirably staying on through the sale of ASF in 1994. There were other long-term employees of ASF that contributed greatly to the ASF turnaround effort and stayed for the duration. Their names can be found in the American Savings of Florida Chronology linked just three lines below.

I hired Carlos Fernandez-Guzman, local Miamian, as head of ASF Marketing. Carlos prepared the ASF Chronology document, 1986 to 1994, from public sources linked here: American Savings of Florida Chronology | Stephen DeWitt Taylor. Carlos, after the sale of ASF to First Union Corporation (FUNC) become head of the Chamber of Commerce in Miami.

Michael Basile, of Stroock, Stroock, and Lavan law firm, was the bank's regulatory attorney. He helped greatly by facilitating a strong, open relationship between ASF and the bank's regulator, The Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), headed by Jack Ryan, in Atlanta. Rick Riccobono, Ryan's 2IC, was an active player in the relationship between ASF and the OTS.

Fixing ASF - 1991 to 1994 - The Plan

Over the course of the next four years, with the support of the bankruptcy trustee, board members and the regulators, I, with the help of my able team, applied the fix-it formula that I had presented to ASF's board of directors prior to being hired. We reformed the governance process, restructured the balance sheet, updated back-office systems, rationalized costs, got risk management (interest rate and credit) under control, and implemented business development programs (like home equity lines of credit) that ultimately led the business to sustained profitability by 1994. Pleased with ASF's performance, the OTS withdrew the cease-and-desist order it had imposed on ASF on 21 December 1990 on 01 March 1994. ASF was now ready to sell or merge on the open market or to continue operating as a viable going concern.

Above: Jack Ryan, Regional Manager, Atlanta, Office of Thrift Supervision, 1990 to 1994.

Above: Rick Riccobono, here pictured as Acting Director of the OTS testifying before Congress in 2005. Riccobono was 2IC to OTS Atlanta head Jack Ryan, from1991 to 1994, the period of ASF's turnaround.

ASF - Denouement

In early 1994, ASF's turnaround having been accomplished, a forward earnings trajectory established, and the regulators being satisfied that ASF was on solid ground, Enstar bankruptcy trustee and ASF board chairman Rod Fraser, was keen on putting ASF up for sale. During April of 1994 Enstar issued a letter to ASF's board of directors affirming its desire to put the bank up for sale. The regulator, Jack Ryan, was in support of selling as well, but the other shareholders (60%) had a right to their say. Accordingly, I persuaded Fraser and Ryan, to approve the organization of a committee of independent directors to represent the minority shareholders. The existing board members were all selections made by the bankruptcy trustee.

In March of 1994 I identified three qualified outside people acceptable to the regulators and the bankruptcy trustee to join the board to form an Independent Committee to represent the minority shareholders. The three board members comprising, with current Enstar appointed director Bill Dukelow, the independent committee of the board were Dr. Barbara W. Gothard, Donald T. Senterfitt, and Erwin Allen.

I was determined to ensure that the optics of ASF's path forward would be seen to be beneficial for all ASF constituencies. The Miami law firm of Sacher, Zelman, Hartman, PA, with point people Barton Sacher and Cy Hornsby, very ably represented the Independent Committee. The Independent Committee hired Bear, Stearns to conduct a full review of ASF's five-year business plan to establish baseline valuation parameters and to assess ASF's capacity to move forward as a going concern.

Above: Bart Sacher, Sacher, Zelman, Hartman, and Paul law firm.

In early April 1994 Enstar formally notified ASF's board of directors that it wanted to put ASF up for sale. On 24 May 1994, upon recommendation of the Independent Committee, the full board voted to select Goldman Sachs as ASF's financial advisor. Goldman partner, Chris Flowers, represented Goldman Sachs on the sale. Interesting, Chris was from Alabama. He perpetuated the Alabama connection at ASF with Marvin Warner and Rod Fraser both being Alabamians.

On 20 June1994, Goldman Sachs began a search for potential buyers of ASF. In late July Goldman met with the Independent Committee to review preliminary indications of interest. Throughout August and early September, three potential buyers did due diligence at ASF. Another potential buyer had not been invited to do due diligence at ASF. That potential buyer renewed its interest in a purchase of ASF. The top bid, at $21 per share, came from First Union Corporation (FUNC).

On 27 September 1994 the Independent Committee recommended to the full board that the FUNC offer be rejected. During the next week, the board met to hear reviews by Goldman Sachs and Bear, Stearns outlining valuation for a sale and potential for ASF to move forward as a going concern. Numerous discussions continued through October. During this period FUNC did not return with a higher bid.

On 01 November 1994 ASF issued a press release notifying of its intent to keep ASF running as a going concern. The release stated that ASF could continue to review its strategic alternatives.

On 23 November 1994 FUNC approached Goldman Sachs with a strengthened offer. The cash bid remained at $21 per share, but under the revised proposal ASF would not be required to sell its MBS portfolio prior to sale consummation. Also, as compared with the original FUNC proposal, the revised proposal provided greater certainty as to the tax-free nature of the transaction and eliminated the repayment of the Enstar receivable as precondition to close. These new provisions eliminated the risks of ASF shareholders receiving lessor amounts than $21 per share as a result of declining MBS portfolio valuations, tax obligations and complications with Enstar.

On 05 December 1994 ASF issued a press release announcing a definitive agreement to be acquired by FUNC.

Above: Chris Flowers, Goldman Sachs, 1994.

ASF Sale Notes and Anecdotes.

ASF: A going concern?

On 28 September 1994, the day after the rejected FUNC bid, Chris Flowers, the Goldman Sachs point man brokering the sale of ASF, came into my office. Chris said, "well, that was an interesting turn of events. I think you guys rejected a good deal. Steve, you're are builder, aren't you? You seem to be making an argument that ASF has more value as a going concern than from a sale." I replied, "Chris, ASF has great potential as a going concern. Just because Enstar wants to sell ASF that doesn't mean the bank should be sold willy nilly. The minority shareholders need representation as well as Enstar and they, represented by the Independent Committee should know that ASF is worth more as a going concern than the anemic bid that was rejected by ASF's independent board committee. The Independent Committee did its proper job in rejecting this deal."

Thrift Advisory Board to the Federal Reserve Bank.

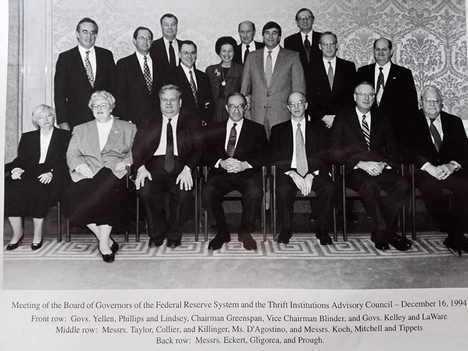

Thanks to a recommendation from OTS regulator Jack Ryan, in 1993 I was appointed to join the Thrift Advisory Board to the Federal Reserve Bank. Before ASF was sold year end 1994, I made eight quarterly visits to the Eccles Building, Fed Headquarters, in Washington D.C. At those meetings, seated around that famous, oval, shiny wood conference table, I and several other heads of S and Ls around the US, would give a business update for our respective markets to the Fed Board of Governors.

Above: Image of Thrift Advisory Board to the Federal Reserve Bank and Fed Board of Governors. 16 December 1994. Me, back row left.

Buyer-Seller Meeting - Shepard Returns

Shepard Broad, ASF's founder, accepted my invitation to attend the Buyer-Seller Meeting at year end 1994. It was appropriate that he attend at the end of ASF's forty-four year long run since he was there at the beginning. Shepard was eighty-five and would live six more years. Though Shepard no longer had anything to do with the bank he founded, his impact on Miami and South Florida extended well beyond that of being a banker and a lawyer. He was the developer of Bay Harbor Islands where he was mayor for twenty-six years. He built the 125th street causeway. Shepard was a member of the Board of Governors of The Shepard Broad College of Law at Nova Southeastern, University. He was a major donor to Mt. Sinai Hospital on Miami Beach where a wing of the hospital was named after him. While at lunch with Shepard at Joe's Stone Crab, he asked me which single individual was most responsible for Miami's success. "I don't know, Shepard," I said. "Fidel Castro," Shepard replied. "They should put up a stature of Castro in Miami's Bay Front Park." Clearly the Miami Cuban diaspora has been central to Miami's success and therefore, at least indirectly, linked to ASF's recovery.

Success Defined

The four years spent at American Savings of Florida was an altogether a successful effort... for the Enstar Bankruptcy Trust... for the minority shareholders and for the turn-around team. Over the course of four years (1991 to 1994) we took ASF from a regulator supervised institution under an OTS Cease-and-Desist Order, selling at $0.17 a share to an acceptably rated (by OTS) institution, sold in 1994 to First Union Corporation, for $21 a share. Many lives were changed for the good due to ASF's successful turnaround.